Airliners Continuously Flying by This Morning

Concorde is, of course, a well-remembered aircraft. It could fly at speeds over twice the speed of sound, cutting London to New York flights down to under three hours. Flying supersonic creates a sonic boom, though. This limited Concorde's operations and will likely do so again when the next supersonic aircraft take to the sky.

Flying faster than sound

Supersonic flight was first achieved in 1947, with a US military prototype Bell X-1 aircraft. It has become common, of course, in military aircraft, but only two commercial aircraft have ever managed it.

Concorde was in service for 27 years from 1976 with British Airways and Air France. Only 14 aircraft entered service with these two airlines, despite initial options for around 100 aircraft from 18 airlines.

Reaching supersonic speeds was an impressive engineering achievement for such a large aircraft. The design adaptions included a delta wing design, improved turbojet engines with afterburners to reheat exhaust, an adjustable nose to reduce drag, and reflective paint to deflect heat.

The only other commercial supersonic aircraft, the Tupolev Tu-144, launched just before Concorde but was not as successful. It was even more inefficient (relying on afterburners throughout flights for supersonic speed) and only ever served one commercial route, from Moscow to Almaty. Aeroflot ended passenger service in 1978 after a crash. After that, the aircraft was used for research and cargo flights and finally retired in 1999.

Breaking the sound barrier

One of the features of supersonic flight is the 'sonic boom' that occurs when the aircraft exceeds the speed of sound. This loud noise has been a severe limitation for supersonic aircraft, with many countries (including the US) not permitting supersonic flight over land.

It is not just an instantaneous sound that occurs as the aircraft actually passes the barrier. It is continuous after exceeding the speed of sound, trailing the aircraft. Although, as speed increases, the 'cone' of shockwaves tightens, lessening the impact on the ground.

The sonic boom occurs as the aircraft reaches the speed of sound or Mach 1 (relative to the air around it, not ground speed). The speed of sound changes with altitude and temperature. At sea level and standard atmospheric conditions, the speed of sound is 345 meters per second (equivalent to 770 mph or 1239 kph). At 35,000 feet, this could be reduced to around 295 meters per second (660 mph or 1062 kph).

It is, of course, not just aircraft that can break the sound barrier and create a sonic boom. A bullet from a gun, or a cracking whip, can produce the same effect.

Stay informed:Sign up for our daily and weekly aviation news digests.

How does the boom occur?

A moving aircraft produces sound waves as it advances in all directions. At lower speeds, these move away faster than the aircraft is traveling. As it approaches Mach 1, waves in front of the aircraft accumulate and compress, increasing the pressure. This pressure creates additional drag that the aircraft has to overcome or 'break through.'

The boom occurs as the waves compress into a single shock wave. This creates a loud boom as this high-pressure shock wave reaches the ground. The sonic boom is, in fact, a double boom sound. This happens as there is a boom when the initial high-pressure shockwave is heard and another when the pressure returns to normal for the listener.

Supersonic without breaking the sound barrier

It is possible to fly faster than the speed of sound without breaking the sound barrier or experiencing this sonic boom. This happens when atmospheric conditions and wind cause a higher ground speed. It is the speed through the air that causes the sonic boom. So if an aircraft traveling at, say, 600 mph experiences a 200 mph tailwind, it would exceed the speed of sound relative to the ground, but not the air.

This is exactly what happened in February 2019, when a Virgin Atlantic flight reported the fastest ever speed for a non-supersonic aircraft - boosted by a tailwind. Similarly, British Airways took advantage of a tailwind during Storm Ciara in 2020 to fly the fastest subsonic transatlantic flight to date, with a Boeing 747.

Breaking the barrier once again

After a long wait since the retirement of Concorde, commercial aircraft may soon be flying supersonic once more. Several aircraft are being developed that could bring supersonic travel back to airlines and private aviation as soon as 2029.

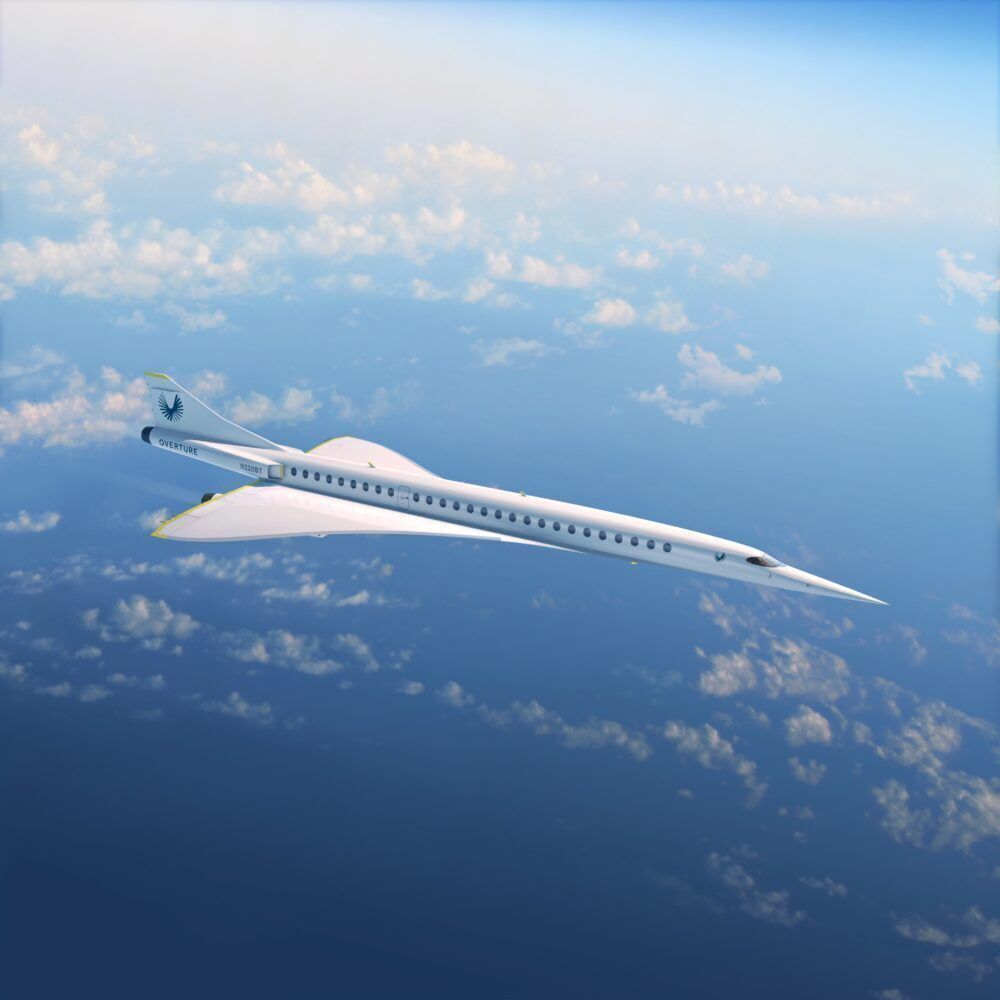

The furthest ahead of these is Boom Supersonic with the Overture aircraft. This would be a premium cabin aircraft with a capacity of 65 to 88 and a range of up to 4250 NM (4888 miles). A prototype aircraft has been developed already, and orders have been placed for the aircraft. This includes an order of up to 50 aircraft from United Airlines.

Boston-based Spike Aerospace has released plans for a business jet with a capacity of 12 to 18 passengers and a speed of Mach 1.6, with much higher range.

Looking further ahead, experiments are underway to develop a supersonic aircraft that can operate without generating a sonic boom. This would open up so many more routes to supersonic travel. Lockheed Martin is working in partnership with NASA on the X-59 QueSST (Quiet Supersonic Technology) supersonic jet. This was targeting test flights in 2021 but has been delayed.

The sonic boom has hindered supersonic flight development in the past and likely will do so again. Are you excited about the potential return of supersonic flight, or do you think it will once again fail to be a commercial success? Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments.

Source: https://simpleflying.com/aircraft-breaking-sound-barrier/

0 Response to "Airliners Continuously Flying by This Morning"

Post a Comment